SUSIE LAU ON IDENTITY & ACTIVISM

“Where are you from?” “But where are you from-from?” This line of questioning will be familiar to many like me, born in the UK or some other predominantly white society but bearing a face that immediately communicates “foreign”. It has the appearance of innocent curiosity that hides its way of othering the person the question is directed at. I’ve lost count of the times I’ve been asked it.

My default deflective answer is “London”, where I was born and have lived all my life, but often people will persist and try to box you in somewhere else. Sometimes, if I’m feeling sassy, I might say Camden, where I grew up. But where am I really from-from? As a British-born, second- generation daughter of immigrant parents who came to the UK from Hong Kong in the 1970s, the question took on new meaning over the past few years, when political upheaval and racial tensions came to the fore. When normality was suspended. When not being able to physically see or touch family created chasms in my life that made me want to root myself to my culture. When I found myself both embracing my culture and confronting the conflicts between the place I call home, London, and the place where my roots lay, Hong Kong. PRE-PANDEMIC, 2019.

Remember those times? Remember when our faces were unobscured? Remember when vaccine passports, pingdemics and loo-roll shortages weren’t in our regular everyday vernacular? Most of all, remember when we travelled freely, open borders and open minds? It was the year I went everywhere, clocking up six months away from London, bouncing from fashion week to fashion week. It was a year of cruise shows, press trips, elongated stays in Hong Kong where my parents are from, and across Asia in general. I was also newly separated from my former partner, and was grappling with co-parenting our four-year-old daughter. The year was spent learning, leaning and yearning for a new chapter. It couldn’t have been larger as a year in any sense of the word.

Then 2020 rolled in. Business as usual until March. After the round of autumn/winter shows in Milan and Paris, talk of this then-mysterious “virus” which had purportedly emerged from Wuhan. China was finally making its virulent rounds on the front row. Masks were slowly but surely being taken up, and hand sanitiser was being pumped around shows. There was a fair amount of people that were unknowingly infected but still air-kissing and hugging. Immediately after Paris fashion week, I was in Los Angeles, which was still at the time a Covid bubble. On returning to London, we celebrated JW Anderson’s new store opening in a thronging Soho. A few days later, lockdown was announced. I went from donning a silver-and-gold-lamé voluminous dress and sloshing drinks around to an anxiety-ridden, in-limbo attire of casual clothes (no tracksuits for me – just stained slip dresses and cake-crumbed oversized shirts).

At first it was different: I was relishing this “rare” moment without knowing how tough and protracted it would become later down the line. Having the luxury to control the rhythm of my work meant that the beginning of lockdown was indeed a respite. As they did for many people, hobbies suddenly became a thing. I got into impossibly intricate chiffon cakes shaped like cartoon characters. I was throwing myself into wholesome arts and crafts. I had the time to mastermind an Easter egg hunt trail in my house for my daughter, Nico, to follow. This would not have happened in any other year. The act of seeing and experiencing fashion in person was suddenly obliterated.

Fashion began to take a Zoom-relegated backseat. The 2020 cruise collections that would have taken me to Japan, San Francisco and Capri came and went and I got stuck into watching things online, albeit with my friends – Bryan Boy, Tina Leung, Tina Craig, Veronika Heillbrunner, Yoyo Cao and Xenia Adonts – and I figured out how to do it collectively over IG Live.As work was pivoting to a deskbound routine of Zooming, writing and creating content at home, I found myself hatching a plan with my friend, Yandis Ying, whom I met through our daughters going to the same nursery in north London. Yandis is from Hong Kong and we bonded over conversations in Cantonese and, more importantly, food. At a time when we were both supposed to have been travelling to Hong Kong to see family we were both looking for a new creative outlet. Something that could connect us back to her birthplace, and the place that many of my family members still call home.

And so Dot Dot came to fruition during the first lockdown. It would be a bubble tea and waffles shop on Stoke Newington Church Street, specialising in flavours that remind us of Hong Kong – like coffee-tea, a local caff staple. Bubble waffles are a Hong Kong street snack which have this distinct semi-spherical pattern. The “roundness” of the food and drinks had this poetic synergy in Chinese, as the character for “round” can also mean togetherness and unity, particularly pertinent at a time when so many had been separated from their families. The shop’s name also comes from a Chinese idiom, 点点滴滴 (“little by little”), which sounds a bit like “dot dot” when spoken aloud and is used as a phrase to describe life moving along bit by bit.

Fitting for a period in which time seemed to have slowed down. There was something more significant for me on a personal level: the food and beverage industry was not new to me. I grew up above my parent’s Chinese takeaway in Camden, and waitressed at the restaurant they later ran when I was in my teens. The trajectory of “Chinese takeaway” kids is that they might work in the takeaway, taking orders in their more fluent English, but on the side they’re also supposed to study hard so they can eventually free themselves from taking on the graft of a Chinese takeaway, which enabled my parents to have a home in the UK but for them wasn’t a prestigious line of work. They wanted me to soar academically and enter the professional classes. But to return to that industry is also an acknowledgement of pride.

I am that Chinese takeaway kid doing her homework at the back, and I do come from a food-obsessed family culture where the thickness of dumpling skins is dissected at dim sum meals. It’s through second or third-generation kids like me and recent waves of east and south-east Asian immigration that new creative food businesses like London’s Dumpling Shack and Bao have sprung up, introducing foods with traditional origins through new spins and interpretations. Dot Dot opened its doors in November amid tightening restrictions in London, but being takeaway-only we were still able to operate. It’s been a process of learning on the job but also of reinitiating myself in the food industry – serving customers, dealing with supply and stock issues and running an efficient business.

Our team members also all happen to hail from Hong Kong, having come to the UK through its latest British National Overseas (BNO) scheme. They are aligned with the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong, as China pushes to impose an increasing number of restrictions and draconian security laws on the former British colony. Learning about their first-hand experiences of a city that has changed so fundamentally has been enlightening and inspiring. Just being able to converse in Cantonese at length and discussing nostalgic flavours of Hong Kong, where food culture is so integral to identity, is part of the joy of Dot Dot. People have been surprised that I’m sometimes in the shop doing food prep, making waffles and taking orders, but being physically hands-on at a time when everything is so digitally geared has been rewarding.

While I was exploring my Hong Kong roots by venturing into a new field, the global wave of lockdowns brought on by Covid was having a terrifying effect on how east and Southeast Asians (ESEA) were being seen and treated in the western world. By early 2021, violent crimes being perpetrated against Asian-Americans were being documented meticulously on social media, reported by media platforms like NextShark. CCTV footage of often-elderly Asian citizens being mindlessly and violently attacked while going about their business was emerging on a daily basis. And then, March 16th. A year on from the beginning of the pandemic.

The most horrific of murders perpetrated against eight victims, six of whom were Asian, by Robert Aaron Long in Atlanta. You can adapt, please and integrate as much as you like. You can speak English with the glassiest of accents. You can “contribute” to society and fall into the model minority myth of being the hard-working, law-abiding immigrant who strives for excellence, but still get gunned down because the shooter was having a “bad day”. The victims’ names – Xiaojie Tan, Daoyou Feng, Hyun Jung Grant, Suncha Kim, Soon Chung Park, Yong Ae Yue, Delaina Ashley Yaun, Paul Andre Michels – I’ll remember forever as I later read them out in a Say Their Name remembrance service organised by Hackney Chinese Community Centre over Zoom.

In the immediate aftermath, I kept waking up with a feeling of dread. It was a dark malaise that I couldn’t quite shake. Something inside of me was triggered to action. Together with vocal Asian American figures like Phillip Lim, Prabal Gurung, Eva Chen and Michelle Lee, I was galvanised into raising awareness and fundraising for victims and grassroots Asian organisations. Speaking about the #StopAsianHate movement on IGTV was an emotive experience, so much so I found it difficult to look into the camera. My voice was wavering and I was visibly tearing up because it is so personal. My experiences growing up, even in an ostensibly multicultural city, were flooding back.I thought about all the times my race and culture has been fetishised in my personal life.

I thought about the thousands of times I’d been cat-called on the street with “Konnichiwa”, “Ni Hao” or guys slow-riding up to me in their cars going, “Hey China, hey China, wanna get in?” I thought about the times I’ve been shouted at to “Go home! ” when I was under the impression that London was my home. I thought about so many in my family and beyond who work in hospitality, and have been abused in their workplace by drunken parties that get lairy after they don’t get their chicken chow mein. I thought about how, even in the liberal context of fashion, I’ve felt the pressure to conform, assimilate and fit into a largely white-dominated environment because I should just be grateful for being given a seat at the table. Then I thought about how vehemently I would not want my daughter to feel at all othered in these ways as she grows up. It’s been a cathartic unleashing of buried feelings.

What gave me even more strength to be vocal about racial injustice towards Asians was the coming-together of women of East and Southeast Asian origins – mostly London-based, working in creative fields – on an instant messaging app. We were strangers, but our experiences were shared and there was an immediate feeling of sisterhood. And so ESEA Sisters was formed, a safe space for confiding with each other about our experiences and trauma while collectively celebrating our cultures through food meet-ups. (When outdoor dining was introduced, we had a fair few dim sum meets.) We also coordinated public campaigns such as a petition directed at The Sunday Times for printing a front-page story on the Duke of Edinburgh’s death which contained the line “Prince Philip was the longest-serving consort in British history – an often crotchety figure, offending people with gaffes about slitty eyes, even if secretly we rather enjoyed them”. Our vision for how we would like to be seen on our terms has only just begun, and I’m so excited to discover where this ESEA Sisters journey leads us.

In the realm of fashion, I now have a greater impetus and belief that the open borders and globalised state of creativity is where the future lies. Fifteen years ago I was blogging about obscure designers from Bangkok and Buenos Aires on Style Bubble – today, that same mindset takes on a renewed purpose. More than ever, I feel that fashion’s ivory-tower, elitist mentality isn’t fit for purpose for the 21st century. That true diversity and inclusivity enriches our industry and shifts it from the rarefied world it was for the most part of the 20th century. That the lived experiences of everyone need to be heard and accounted for, and that together we have great power to enact real change. If I’m ever in a professional situation where I feel cultural “gaffes” are being bandied around, I now have more courage to speak up. If 2019 was the year I went everywhere physically, then the year beginning March 2020 was the moment I travelled deep within my mind to feel rooted to my culture.

To be truly proud of my upbringing, my family and my background, and not to cower or shrink away from it. How it has taken two decades to do so gives one pause for thought, but perhaps it was this tumultuous period of time that forced the issue to the fore. We’ve all had to undergo processes of reassessing, re-evaluating and rediscovering aspects of our lives. For me, it’s been an internal reckoning with a part of me that was buried because I never had to confront it. The world has changed. How we see racial injustice and prejudice has changed. Over the summer, I gave a speech alongside my fellow ESEA Sisters at a Protest to Protect Asians march and said this:

“We now know that collectively, through finding our voices together, we are strong enough to take on entrenched attitudes in established institutions. I have been given the strength to speak up. From private conversations to public collective action. These are our lived experiences. And we are SILENT NO MORE.”

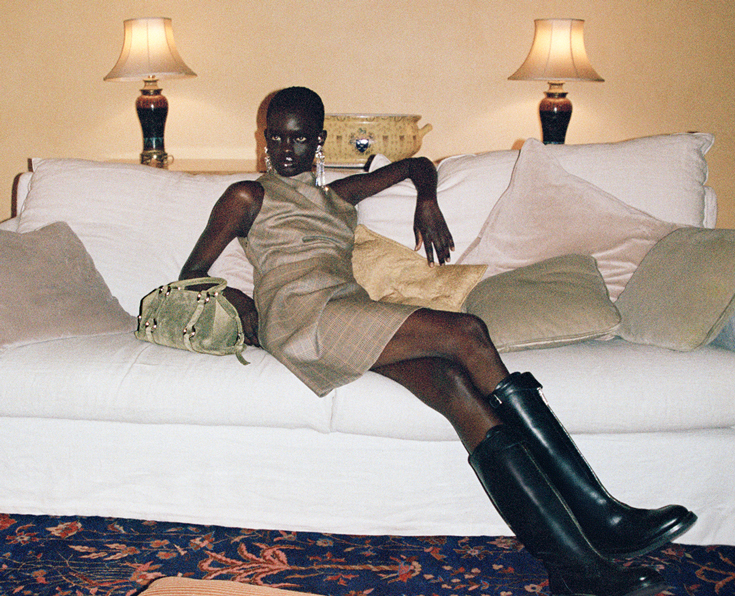

Portrait by Anna Stockland. Taken from Issue 18 of 10 Magazine Australia – BOLD & BEAUTIFUL.