Nightcrawlers: The Future Of Club Culture

Is nightlife dying? Is club culture dying? Are clubs dying? Over the past couple of years, newspapers, magazines and podcasts have been asking these same questions over and over again. The big night out is a relic of the past and it’s hard to find a pub that stays open past 10pm in the capital. Right?

These are all valid questions, as UK nightlife is certainly facing real issues. And it’s ironic given that Charli xcx’s Brat, an album largely dedicated to club culture and “bumpin’ that” in sweaty bathrooms, was the defining record of 2024. At the same time, daytime listening spaces have been having a moment – rooms in which you can sit and take in music loudly via high-quality sound systems – as have record clubs, the most popular being DJ Colleen ‘Cosmo’ Murphy’s Classic Album Sundays. Books about dance music, such as Emma Warren’s Dance Your Way Home: A Journey Through the Dancefloor, are being released left, right and centre in what The Quietus dubbed the “academisation of rave”. Many festivals, such as Glastonbury and Reading, now have big dance line-ups while Boiler Room sets and dance music influencers are populating our TikTok feeds. But living, breathing nightlife is in decline. What’s going on? Dancing in darkened rooms isn’t just a hedonistic way to blow off some steam at the weekend. For many people, it’s a space for marginalised communities to gather. And it has clear mental and physical health benefits: a 2024 study found that dancing may treat depression more effectively than medication. Berlin is a city that acknowledges the cultural prestige of electronic music, with techno now placed under Unesco’s protection, but the UK hasn’t got there yet.

Here, supermarket-sized clubs are very much thriving: Manchester’s Warehouse Project and North London’s Drumsheds, to name just two. But grassroots venues are finding it tough. In September last year, the Night Time Industries Association revealed that between 2020 and 2024, a staggering 480 nightclubs closed their doors in the UK. “We think there’s an impact from the mass commodification of night life,” says Robbie Bloomer, who with Marcos Navarro created High Hoops, a queer night based in Manchester that books homegrown and international talent, and has an inclusive ethos. “The electronic music scene has gone mainstream in such a huge way over the last few years and, due to an increase in big venues with huge budgets, many younger people are facing sky-high ticket prices, leaving them less able to afford going to smaller venues,” says Navarro. He insists that this trend can create opportunities. “Operating in tough economic situations has often forced creatives to think outside the box and adapt.”

That much is true for Bristol based Club Djembe, an event that specialises in platforming global club sounds from amapiano to UK funky. One of co-founder Jake Knight’s favourite moments happened during a socially distanced night out at the height of the pandemic. It was a sitdown rave, “and the vibes were immaculate”. “Next thing we know, people are dancing on tables and generally having too much fun. There was only so much we could do before security just started kicking everyone out.” DJ Polo, a Bristolian hero who helps run the night, has been seeing the opposite of the ‘nightlife is dying’ narrative this past year, citing the packed nights at Fabric and Koko that he’s played. “They’ve been rammed, and with really good energy. Clubs that innovate, stay authentic and cater to diverse audiences will always have a place.”

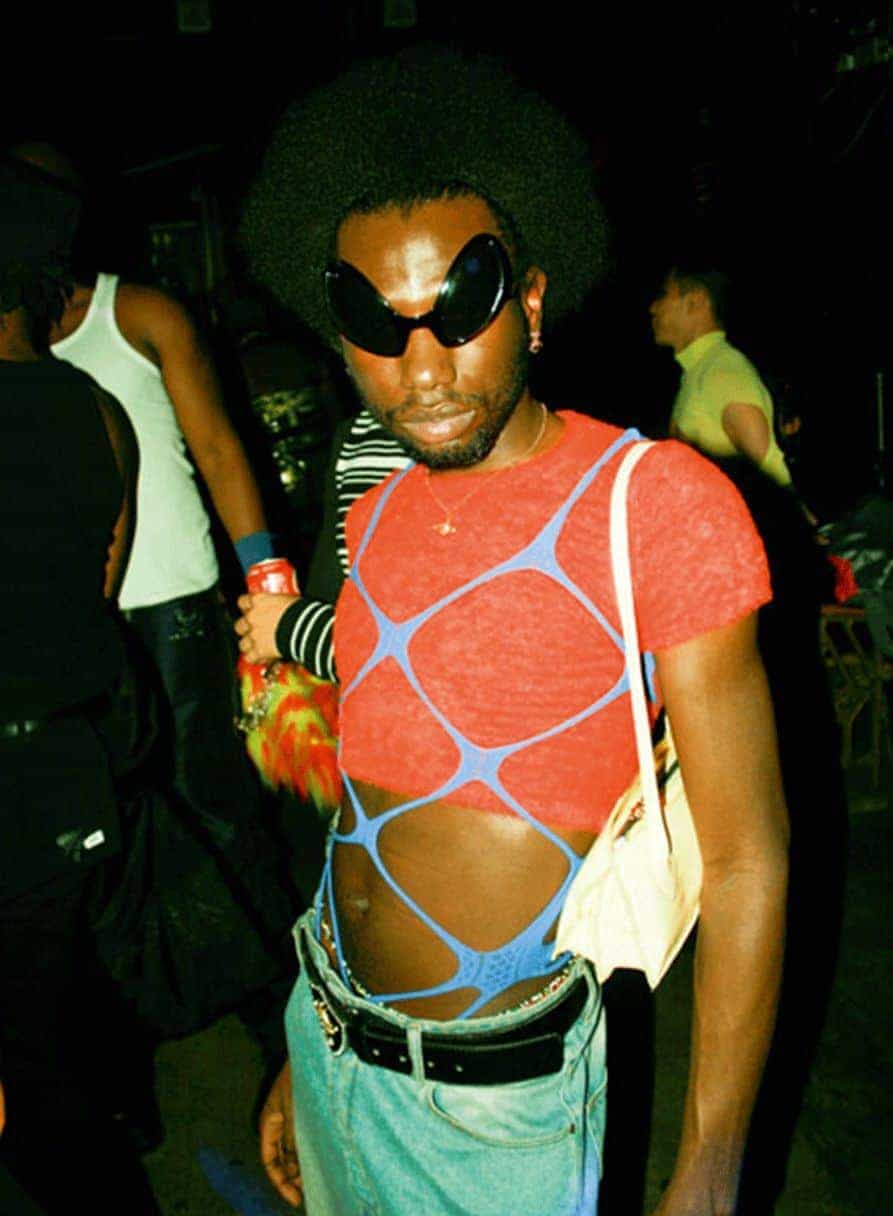

Nadine Noor from Pxssy Palace, London’s party series for queer, trans and intersex people of colour, agrees. Nightlife isn’t dying, you just have to know where to find it. “Compared to 10 years ago, when we started, we have a lot more choice, with niche and underground nights starting up,” they say. Originating as a house party, Pxssy Palace has grown into a globally recognised brand. Noor describes one of their favourite memories: when a power cut struck at one of the PP parties, attendees sang Crystal Waters’s house classic Gypsy Woman (La da dee la da da) a capella, refusing to let a technical hitch ruin their night.

Like Pxssy Palace, Glasgow’s Ponyboy is a night carving out a haven for queer and trans people to dance and express themselves. With its name taken from the 2017 Sophie track, Ponyboy is not just a night but a performing collective. Their events build worlds, with the next party planning to bring in designers to create custom looks for ‘cast members’. “We’ve also been hosting pole classes ahead of events, facilitated by [artist] Krystal Spikes, and are generally finding ways to contribute to an event more special than the last,” says Dill Dowdall, who co-founded the club with Reece Phimister. Ponyboy has also established a network of creatives that might not typically work within club spaces: makeup artists, SFX artists, nail techs, ballet dancers, “and this community is constantly expanding”, says Dowdall. It’s a formula that works: in two years, Ponyboy has jumped from 150-capacity spaces to 800 and regularly sells out.

Club Djembe started out because its founders had a desire to create an event that didn’t feel “exclusive”, says Knight. “We wanted to put on a wild party in a bar. All that mattered was the music being on point and that the venue [Bristol’s The Love Inn] would have us back again. We’re also really into cocktails, so we always had a signature drink for each event for a fiver – an absolute steal. By the third party we had more than 10 DJs who wanted to go back to back all night. It was carnage and the bill for the rider was huge. That hasn’t changed!” High Hoops has come a long way from its first birthday in 2016, hosting Honey Dijon in a 200-capacity venue. “It’s quite surreal to think of her playing in a space like this now!” says Bloomer. They programmed American deep house proponent DJ Sprinkles’s Manchester debut and have enjoyed a Pride weekender at fabled venue The White Hotel in Salford for the past six years. Many of these nights have a philanthropic slant, with fundraisers for friends and important causes at the heart of what they do – High Hoops has raised more than £50,000 over the last four years.

But with all the gold-standard nights the UK has to offer, from Trance Party to Adonis and Ape-X, we shouldn’t gloss over the fact that nightlife is struggling. Naomi Momoh from Rat Party, a bimonthly, queer-run event in Leeds, believes there’s “a big disconnect between nightclubs and DJs. Clubs are struggling to keep up with the financial cost of booking certain DJs and people are generally going out less, which we’ve noticed over the years since we started throwing our nights, so it’s a real struggle for clubs to break even.” Dowdall from Ponyboy says they were almost made homeless at one point and have had to give up their creative studio to sustain how much the events were costing. “It’s been a lot of stress and sacrifice, and not always knowing whether we’ll survive.”

But another club founder is looking beyond the doom and gloom. “I believe that nightlife is evolving, not dying,” says Elianne Mahay-Goodrich, the force behind London’s Flinta-focused party Leztopia (Flinta being an acronym for female, lesbian, intersex, trans and agender). “While the challenges are undeniable, from Brexit to rising operating costs, noise complaints, licensing issues and shifts in how people engage with events, there’s still a huge need for these spaces. The desire to connect, dance and celebrate individuality in club spaces will never disappear. It is woven into the fabric of London and won’t go away any time soon.” She adds that many parties trying to run at the moment are being cancelled before they even happen due to low ticket sales, “meanwhile, the UK music industry was recently valued at £7.6 billion…”

“A general lack of respect for arts that are birthed through the underground only gets more complicated when you’re creating space for a community that is already at the end of constant scapegoating,” says Dowdall. She calls for more funding for nightlife and also for ravers to “consider where they put their money – we’ve seen the power of boycotting recently and similarly we have collective power to sustain promoters and venues with the right intentions.”

Noor thinks that licensing reform is the answer, as is ensuring nightlife workers are paid properly, since 17 per cent earn less than the London Living Wage. “Established DJs should be making an effort to play in smaller clubs, focusing less on an individual mindset and supporting the culture. And for those who don’t work in it, and can afford to pay, stop asking for guestlist!”

Many of these nights see the commercialisation of dance music as a factor in the scene’s struggles. “Over the last few years there’s been a huge rise in these massive shows, with brands rushing to [use] dance music,” says Knight. Vast amounts of money are pouring into branded line-ups, such as Charli xcx partnering with H&M. “It’s become less about discovering new music or local scenes,” Knight says.

Sorry to say it, but if you believe that club culture is dying, you’re just not looking hard enough. Have a scan through Instagram or Resident Advisor listings and you’ll eventually strike gold. Knight mentions some of the smaller clubs that are creating exciting, inclusive spaces: Bristol’s The Love Inn and Strange Brew, Manchester’s The White Hotel, Soup and Stage & Radio, and South-East London’s Ormside Projects. “When I look around and see a room full of people dancing, smiling and unapologetically being their true selves, that’s my favourite part,” says Mahay-Goodrich. It’s more important than ever to support your local club night. We’ll see you front left.

Taken from 10 Men UK Issue 61 – MUSIC, TALENT, CREATIVE – on newsstands now.

Text FELICITY MARTIN

Photography courtesy of RAT PARTY, CLUB DJEMBE, HIGH HOOPS, LEZTOPIA, PONYBOY AND PXSSY PALACE (LUCIAN KONCZ CREATIVE, KWXME, BLUE)