FROM THE ISSUE: DIOR, SAVOIR FAIRE

What is craft without purpose? For Dior’s Maria Grazia Chiuri, you can’t have one without the other. In her eight years at the house, the designer has supercharged the conversation around savoir faire, re-energising house traditions and forging new creative collaborations. But for Chiuri, the point of all that artisanship isn’t to justify a designer price tag. She sees craft as a force for good and a way to uplift artisans and their communities.

Since Chiuri’s debut at Dior in 2016, she has thrown the weight of one of the world’s biggest luxury houses behind a desire to create feminist ways of working, living and sharing, as well as dressing. How things are made matter to her. The beating heart of craft at Dior is found in its Paris couture ateliers, where a commitment to beauty, excellence and handmade perfection is paramount. Here, teams of petit mains pour a lifetime of experience into what they produce, with skills passed down through generations. For Chiuri, this is where everything starts, and she’s hands-on. “For me, the atelier is part of my job. The other designers used to work only with the sketch, I don’t. To see what is possible and what is not, I do that in the atelier,” she told me when I visited Dior’s ‘flou’ and ‘tailleur’ ateliers for 10 back in 2019.

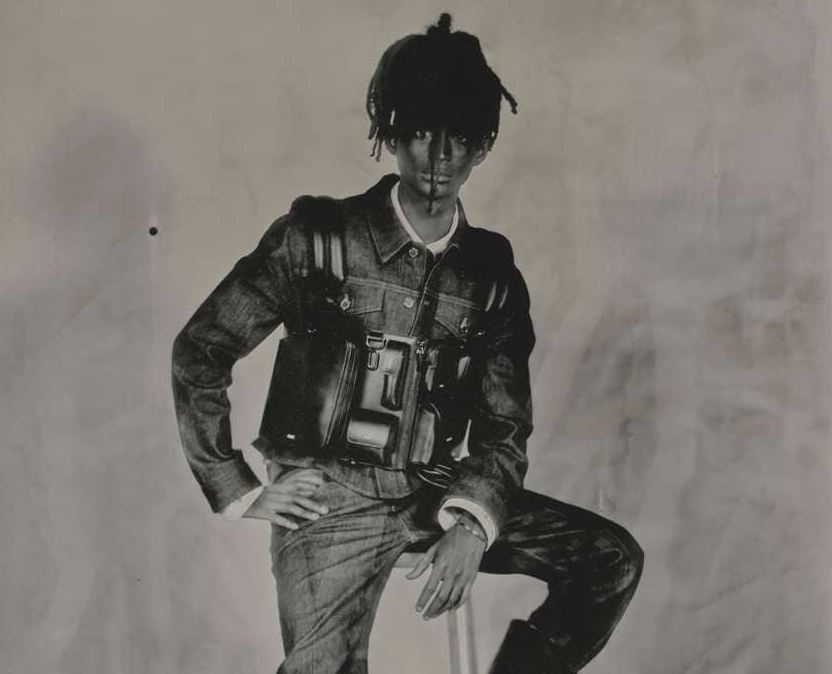

We’ve spoken on several occasions since and each time the conversation has gone back to the importance of savoir faire – the combination of confidence and ability – and Chiuri’s purposeful way of using it. Radiating out from that Paris atelier are the specialist factories in Italy and Spain that produce the brand’s bags and shoes. Its catwalk jewellery, designed by Chiuri, is produced in Italy and Germany. In these ateliers, the knowledge of generations of specialist artisans is brought to the task of realising the designer’s ideas. The famed Lady Dior bag, for instance, is assembled by hand in Florence from 150 separate pieces. The lambskin version pictured on these pages goes through five major stages. After skin selection, cutting, assembly and final stitching, the last stage is euphemistically called ‘pampering’, where the bag is primped and perfected before being sent to stores.

Further afield are the specialist international ateliers Chiuri has worked with on her globetrotting resort and pre-fall shows. The designer sees these travelling shows as an opportunity to forge new relationships, share ideas and create mutual benefits with craftspeople whose values are kindred with Paris couture. “Craft is really a way to make bridges to communities. We can support each other. I think it’s a language too, one which we can use to communicate. This is possible in fashion, especially for Dior,” she told me in 2022. That year, Chiuri showed her resort collection in Seville and sought out local embroiderers and metalworkers who had previously only worked with churches on altar regalia and garments. “There are techniques I found that I have never seen in my life. This is exceptional. This is haute couture, and it was really an enrichment for me to work with them,” said the designer, who later revisited the Spanish artisans with members of her Paris atelier to further the collaboration.

Call it the couture equivalent of friends with benefits but Chiuri’s practice of international savoir faire diplomacy is a win-win. Dior deepens its craft repertoire, bringing different and more diverse emotions to its look, while at the same time using its power to uplift specialist artisans and local communities. Whether that’s embroiderers in Puglia, Mexican leatherworkers or African print makers, the designer finds the values of couture in far-flung places. “Couture means having the specific knowledge to create a unique piece with your hands. Where there are people with the skills to create something with their hands, beautiful things, you can find it,” she says.

Chiuri’s 2019 show over in Marrakech saw her partner with a host of African artisans including Uniwax, which makes a traditional wax in the Ivory Coast, and a Moroccan women’s textile and ceramics association called Sumano, which creates tapestry-like woven pieces. More recently, her PF23 show in Mumbai was a culmination of the deep relationship she has with Karishma Swali, the director of the Chanakya School of Craft, which champions the inclusion of women into a highly skilled industry that has been traditionally a male-only preserve. Churi has worked with Swali for many years, but deepened the relationship when she joined Dior in 2016. Their handwork appears in every Dior collection, alongside embroideries produced in the Paris ateliers of Lesage, Vermont, Paloma, Hurel and Safrane. “The school and laboratory offer salaries, health insurance and childcare opportunities for women,” Chiuri said after the Mumbai show adding, “I think it’s the most satisfying thing I do.”

That layer of emotional care is something Chiuri has brought to the fore at Dior. It sets the tone for her detail-oriented approach to her role at the brand, which is rooted in a sense of responsibility – to do things to the highest standards, creatively and emotionally. For Chiuri, small details communicate so much. The fingers full of antique rings that she habitually wears are a clue that clothes are not the only things close to Chiuri’s heart. Her design roots are in accessories and, for her, details count. She pays as much attention to the design of a T-shirt, beret or bracelet as she does to a gown because the look of the season is distilled into these more accessible pieces. “I work upon all the details of those little pieces because I think it is important that a young girl can buy the earring, the bracelet. It gives people the opportunity to be a part of the Dior family and also have a look of the season with a single piece, with a little charm,” she told me after one show. What pulls it all together is a commitment to craft, even in the simplest pieces. The designer is aware that if you don’t use it, you lose it.

Chiuri has had intimate knowledge of craftsmanship from an early age. Her mother was a seamstress and made Chiuri’s wedding outfit. (The designer, who had a shaved head at the time, refused to wear a big white gown and instead got married in a lace skirt, blouse and cashmere coat.) Savoir faire has been a constant in her long career, first as an accessory designer at Fendi, where she worked with Silvia Venturini Fendi on the era-defining Baguette bag, then later at Valentino, where she and design partner Pierpaolo Piccioli were tasked with making the accessories as desirable as the gowns. They would sit in on couture fittings with Mr Garavani, learning from the master, and eventually succeeded the legendary couturier. Moving their two desks into his old office in Rome, they made their mark with supreme romanticism and stellar accessories, such as the hit Rockstud shoe.

Chiuri joined Dior in 2016, convinced there was another creative chapter for her at the storied French house. Her Dior era has been defined by the force of the female gaze and an intense, activist energy. She’s harnessed the brand’s cultural power and brought a collaborative richness to the creative process. She’s a changemaker who cares about how things are made. Craft matters. Savoir faire is her rocket fuel.