TONY GLENVILLE ON DARK VICTORY

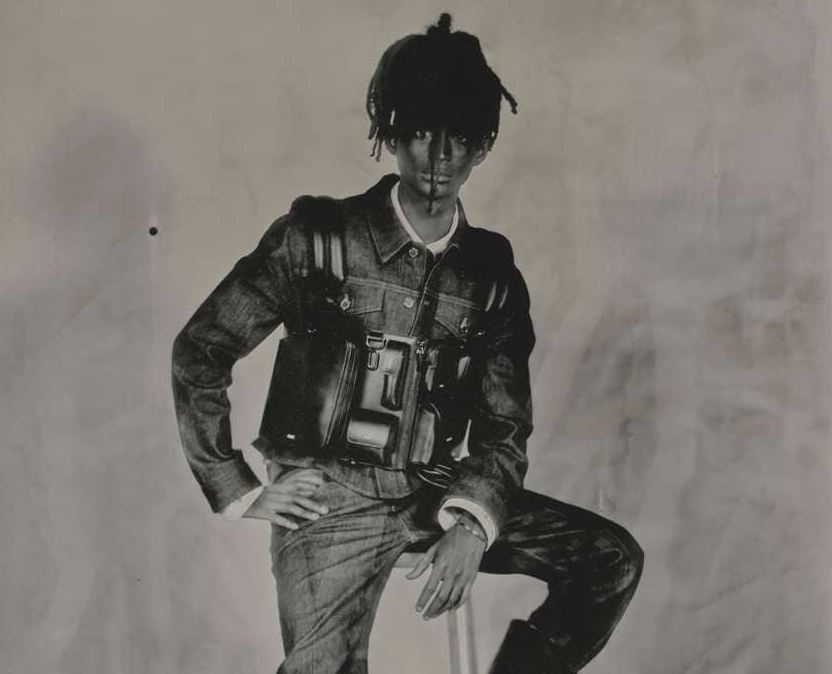

Into the heart of darkness, fashion embraces a narrative that’s ghostly, chilling, romantic, emotional, sexy, aggressive… or simply classic.

The inspirations of this twilight world are steeped in the sombre, sober and reflective, and the darker realms of fairytales, literature, music, film and legends: Mary Shelley, Edgar Allan Poe, Siouxsie and the Banshees, The Cure, Joy Division, Tim Burton, Alfred Hitchcock and F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu.

The narrative is muted, nostalgic, escapist, historical and timeless. Fashion loves making the narrative of lost love, sadness and romance the most memorable story: Vanessa Paradis in a cage for Chanel; Grace Jones hula-hooping in a towering Philip Treacy confection. It is about a seemingly odd juxtaposition, opposites combining and seducing with black leather, straps and buckles with tulle, chantilly lace and satin ribbons. This is gothic at its most fantastical.

The classic, darker moments have been perfectly captured by Peter Lindbergh figures placed in stormy landscapes; Karl Lagerfeld placing a Chanel haute couture show in a ruined and post-disaster theatre; Olivier Theyskens constructing a huge dress out of a flight of circling blackbirds; or, simply, Ann Demeulemeester producing black-based collection after collection, with a tristesse of languor and melancholy that inhabits its own beauty.

The dark arts have inspired some of the strongest of fashion’s memorable moments, while its evocative imagery has provided the source of much inspiration. The dramatic black Royal Ascot of 1910, caused by the death of Edward VII, which inspired Cecil Beaton’s costuming for My Fair Lady 45 years later, was described by Beaton as “giant crows or morbid birds of paradise strutting at some gothic entertainment”; the photograph of the Queen Mother and her daughters, Queen Elizabeth II and Princess Margaret, in misty mourning veils at King George VI’s funeral in 1952; Wallis Simpson in her miraculously made-overnight couture, severe plain black coat and chest-length veil, created by Hubert de Givenchy, who flew from France to the Royal Burial Ground at Windsor and spent all night working on the outfit she wore at the Duke of Windsor’s funeral in 1972; the late Queen Elizabeth II in floor-length black lace visiting Pope John XXIII in Rome in 1961. When Christian Dior died in 1957 the shots of all his house mannequins shrouded in black summed up for many the couture mourning statement.

During the golden age of fashion magazines, photographers Richard Avedon and Irving Penn portrayed fashion in colour, but what we recall are the legendary black and white photographs Dovima with Elephants (Avedon, 1955) and Qui etes vous Polly Maggoo (1966, directed by William Klein, shot on the set of the French film of the same name). They could have been shot in colour but the starkness of the monochrome fits the way Klein wished to communicate fashion through film. Avedon’s Nastassja Kinski Naked With a Python is powerful in black and white and was shot in 1981.

My formative fashion years were seen through film and TV, and all pre-colour. Bette Davis transforming from a plump spinster in frumpy frocks to an elegant voyager; Norma Shearer wearing and carrying off anything the costume designer Adrian threw at her; Celia Johnson’s Brief Encounter, embodying 1940s suburban neatness; Ginger Rogers literally flying through the air in feathers, bugle beads and bias-cut satin. Hollywood used the sharpest of lines in film noir, in celluloid classics such as Gilda, starring Rita Hayworth, and in musicals, too, with Rosemary Clooney in White Christmas. Inspirations like these are classic and still referenced by designers across the world, as great pieces in monochrome are at the heart of timeless fashion.

A favourite piece lies in the collection at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. It was designed by the great couturier Lucile in 1912 and is a precursor of Diane von Furstenberg’s wrap. With just a hint of Morticia Addams, it’s a slender floor-length wrap dress in heavy black crepe, whispering into a slight train, a strong statement piece both for a time when black was worn predominantly for mourning, and by the elderly. The dress may have been made for a widow; it’s described as demi-mourning since it has a narrow white under-layer across the wrap and at the narrow cuffs. However, the widow was surely a slim, seductive one, since the raised waist, narrow silhouette and body-conscious drapery hardly suggest her retiring to secluded, lonely widowhood. Of Lucile herself, according to Cecil Beaton, “her artistry was unique, her influence enormous”. This dress, like many later evening gowns, has the power to evoke an entire narrative about its wearer, part of the power of darkness.

The narratives of fashion and the moods that are constant across the seasons and decades are shrouded in dense inky blacks or black with white; not snappy black and white but in a ratio. Even the muted or mysterious tones evoke darkness and mystery: grey, from charcoal or pewter through mist and fog; the rich brown of bitter chocolate; all the reds from claret and Bordeaux, through to lie de vin, literally “wine dregs”, a truly evocative name. Even nature is gothic in its pine forest green, midnight blue and stormy slate. Colour invariably comes first in the fashion cycle, before the threads or fabrics are woven.

The fabric is the key protagonist in this story, though, setting the silhouette, the movement and the drama in motion. Dense, opaque velvet absorbing the light, cascades of taffeta rustling against marble steps or waltzing on polished parquet, or fragile chantilly lace overlaid on ivory or blush. Of course, there are also deeply draped folds of liquid silk jersey or the flights of mousseline hovering and defying gravity in clouds or the fragile texture of crepe, whose surface elasticity both moulds to and shrouds the figure. The silhouette in black or faux black has a power that pale tones or even white will never have. The definition of a dark shape be it the princess/Cinderella ballgown of a tiny waist and huge full skirt, the severe tailored Dior New Look bar jacket or a neat Chanel pin tucked into a Little Black Dress, “the Ford car of fashion”, it makes the definitive shape statement. Empire line or trapeze line, sack dress or tightly fitted sweater dress, every silhouette responds to be a clear, clean dark outline. The tuxedo in black from the 1920s onwards has a power that no other evening look can match; whether by Yves Saint Laurent in 1966 or Ralph Lauren, it is an enduring winner.

Across the seasons, dark romance and drama has inspired designers, the narrative often encompassing historical or cultural influences or offering the perfect platform for true innovation, perhaps defined by Cristobal Balenciaga, whose Spanish aesthetic and cultural roots were always at play. Yet Claude Montana, Dolce & Gabbana, Hervé Leger, Azzedine Alaïa and Rei Kawakubo are among the collection of designers who have always relished the opportunities that black and more introspective or complex narratives offer in the form of creative rigour. When John Galliano made his “comeback” in 1994 he used only black silk satin-backed crepe gifted to him by Hurel, perhaps all part of the power of Anna Wintour’s all-time favourite show. The story of the show centred around Princess Lucretia, who has returned to Paris as a widow in the early 1920s; her wardrobe is a brooding noire of bias-cut slips and kimonos.

Through the late 1970s, with the arrival of punk, through the New Romantics and even during the flamboyance of Dynasty throughout the 1980s, black threaded its way through even the glitziest of decades. As we entered the 1990s, fashion needed a clean-up after a decade of insane shoulder pads and glittering opulence, Lacroix fantasies and space-age inventions. The advent of the matt-black 1990s, with Helmut Lang and Yohji Yamamoto, dialled it down and began influencing interiors and even food, which was a welcome relief.

Black returns powerfully at intervals, it never truly disappears; sometimes it is seemingly safe and oftentimes naughty. The dark narrative remains victorious over lightness since perhaps the sexy and wicked appeals more than the virtuous. Dig out The Wicked Lady (1945), starring Margaret Lockwood, or watch the Addams Family (1991), not only because she appears to have her own lighting team assigned to follow her, but because Angelica Huston’s immaculate makeup and sinuous evening wear make her a gothic heroine. And of course, seek out the original Morticia, immortalised by Carolyn Jones on TV in the 1960s. Bette Davis’s Wicked Stepmother (her last film, in 1989), Norma Desmond, Maria Callas, Cher in Bob Mackie or the pieces by Alaïa are all about putting the diva centre stage in every drama. It doesn’t matter if it’s chiffon and long, lace and ballerina length or lycra and short, it can be crisp and tailored. As long as it’s black or dark, it’s strong, it’s fashion, it’s Jenna Ortega’s new Wednesday Addams and we love this dark victory.

From 10 Magazine Australia Issue 21, ROMANCE, REBEL RESISTANCE, out now.