KENYA HUNT WRITES ABOUT MENTORING

The idea for ROOM Mentoring came from a series of dinners I had been having with girlfriends who were all in similar positions as me – as in, Black and brown women with relatively senior jobs in media and fashion in London. Unicorns. Because there seemed to be so few of us here. And these dinners were a replication of what I had with my sprawling network of Black girlfriends in publishing in New York City, where I started out in the industry. We would get together after work and on the weekends and laugh, commiserate, plot and plan, compare notes and big each other up. If we were feeling shaky or irritated, doubtful or depleted going into the dinner, we’d usually feel full and restored coming out.

During one dinner – this was in 2015, when I had just started a role at Elle UK – we talked about how overwhelmingly white and criminally homogenous the British publishing and fashion worlds have historically been, and how difficult it is for young graduates of colour to break into both. This followed a similar conversation I had had with Zowie Broach, head of fashion at the Royal College of Arts, in which she spoke to me about the very few BIPOC students she had in her programme.

So I decided to broaden my little support network to include Black and brown students and graduates. My friends and I wanted to see what we could do with the positions that we had to help support the young ones coming through, rather than wait for larger systemic change. Zowie sent a few of her students my way. I connected them with my friends and peers to mentor them and we grew from there.

ROOM began as a mentoring initiative but now I would describe it more as a grassroots support network in which we help aspiring Black and brown creatives and professionals in fashion be as successful as they can be, whether they aspire to work in established, mainstream spaces or grow their own businesses. And I’d argue that those of us who are ‘mentors’ learn just as much from our ‘mentees’.

Navigating any job, studio or school as An Only comes with a lot of what my friends and I call ‘foolery’. And as a Black woman, I am all too familiar with the experience of racism and how it can distract you from going about your life and doing your work, as Toni Morrison famously described it: “[Racism] keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being. Somebody says you have no language and you spend 20 years proving that you do. Somebody says your head isn’t shaped properly so you have scientists working on the fact that it is. Somebody says you have no art, so you dredge that up. Somebody says you have no kingdoms, so you dredge that up. None of this is necessary. There will always be one more thing.” With ROOM, there is no need to explain.

I’ve always believed in the power of coalition and community. Growing up in America, I was surrounded by and benefitted from organisations that were founded by Black people to lift as they climbed and help young Black people to thrive in and navigate overwhelmingly white spaces. For me, those environments included the NAACP’s youth programme, which I participated in as a child; the various Black student coalitions I took part in during my time at the University of Virginia, a largely white institution founded by Thomas Jefferson that is still coming to terms with its slave- owning past; and the gangs of girlfriends that have provided moral support throughout my career. I believe strongly in developing a network in which folks can pool together resources and push one another up.

History is filled with examples of this. In the 1940s, there was the National Association of Fashion and Accessory Designers (NAFAD), a coalition of Black designers founded by Mary McLeod Bethune-Cookman and Jeanetta Welch Brown to fight exclusion by the industry’s gatekeepers and create opportunities for one another. Through their work, its members were able to both build their own empires and reach the mainstream. (The president of the network’s New York chapter, Zelda Wynn Valdes, designed custom gowns for Black socialites and the Hollywood elite, but also became famous for designing the iconic Playboy Bunny costume.)

In the world of art in the 1960s, a band of Black artists formed Spiral, who united to explore what it meant to be Black and creating art during that politically and socially fraught time, opening the door to a wave of alliances that advocated to make sure Black artists gained entry into mainstream galleries and museums. In the world of book publishing, Toni Morrison used her platform as an editor at Random House to help change the make-up of the industry in the 1970s, nurturing the careers of Black authors including Toni Cade Bambara, Henry Dumas and Gayl Jones. And in 1988, Bethann Hardison, a woman often described as the mother of fashion’s diversity movement, founded the Black Girls Coalition to advocate for better job opportunities for models of colour. Later, in the 2010s, she established and led the Diversity Coalition in a successful campaign to demand greater representation on the runways and in fashion as a whole.

In the two years since the murder of George Floyd unlocked a global racial reckoning, we’ve seen a new wave of individuals and collectives rise up to demand that the fashion industry do better, in the same way we saw Black artists challenge the museum world in the 1960s and Black authors take publishing to task in the 1980s. Black folk moving the needle for Black folk. In America: Aurora James’s 15 Percent Pledge; Lindsay Peoples Wagner and Sandrine Charles’s Black in Fashion Council; and Jason Campbell, Kibwe Chase-Marshall and Henrietta Gallina’s The Kelly Initiative, among many others. And in the UK: Rubric Initiative, Fashion Minority Report, Mentoring Matters and FACE (Fashion Academics Creating Equality), to name a few. Not to mention the incredible work of designers like Kerby Jean-Raymond, Telfar Clemens, Samuel Ross and the late Virgil Abloh opening doors for people of colour.

An editor I once interned for described the fashion industry as a business full of outsiders and misfits. It was a statement I found romantic but confusing, because the vast majority of the people I knew who worked for magazines, fashion houses and PR companies would best be described as insiders – daughters, sons, nieces, nephews, goddaughters and godsons of people with power and sway in the business. Or lucky souls fortunate enough to have a family friend or schoolfriend who could make an introduction, pull a string or two. Or people privileged enough to have their families supplement the abysmally low pay that accompanied most entry-level jobs in fashion. And anyway, outsider or insider, practically everyone was white. Fashion was, and to a certain extent still is, a uniquely challenging industry to gain entry into and navigate.

In my case, I was privileged enough to tick off two of those boxes. I had a supportive family. I also had a cousin who recruited for a major publishing house, Time Inc, and a big-sisterly roommate who worked in the PR department for Italian luxury conglomerate Gruppo Aeffe and helped me learn the nuance of the industry. These were two Black women who had learned their own lessons as they struggled to rise up the ranks. My cousin, in particular, would talk to me often about how she had been mentored and helped along by a successful Black woman in the recruitment field. These women paid it forward with me. They taught me how to follow up after a job interview, how to write concise thank-you notes on correspondence cards and showed me the best underground spots to go party and have dinners and see art and hear live music in. They taught me personal finance hacks and how to negotiate my pay.

They helped sharpen both my professionalism and cultural literacy. And when I got my first publishing job, they taught me how to handle both the inevitable disappointments (micro- and macro-aggressions, missed promotions) and highs (fun assignments, pay rises) that came with it. As I settled into the industry, I met other dynamic, inspired women through the course of my work. An interview with Bethann in 2007 led to a treasured friendship that I continue to learn from to this day. And many of the editors I’ve worked for, women and men of all races and backgrounds, have since become dear friends and sounding boards.

If it weren’t for these people who coached and believed in me, during the moments when I couldn’t see past self-doubt or fear, I wouldn’t be here. And my hope is that, in ROOM, we can do that for each other, and in the process contribute a small part to the greater shift happening in this industry.

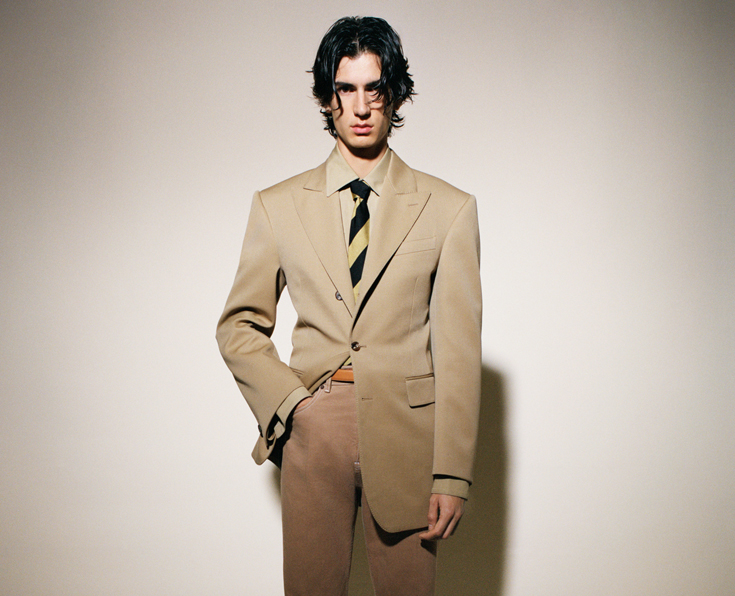

Top image: ROOM members including, Des Lewis, Kacion Mayers, Jessica Skeete-Cross, Eni Subair, Kacey Amoo and Cynthia Lawrence-John, Rubee Samuel, and Carlene Thomas-Bailey.

Kenya Hunt is the editor-in chief of Elle UK.