Inside The Costume Jewellery Renaissance

As the fabulously named Wow Platinum, Aubrey Plaza fizzes through Megalopolis, Francis Ford Coppola’s brilliantly bonkers epic, in a blaze of blistering, oversized jewels. Critics may have hated the film, but so what? The whole thing was such a breath of creative relief that the costume jewellery design deserves an Oscar category all of its own. From Wow’s exquisitely made ‘elasticated’ diamanté chokers to her gold chainmail wig and moulded-brass bra, I think Coppola – ever the stylist – is on to something here: costume jewels are relevant again.

Florence Pugh gets it, too. Though she is often bedecked in serious high jewellery pieces on the red carpet, more recently she has been wearing jewellery from Goossens on Vogue’s cover and at promo events. Possibly the most lauded of all the traditional costume-jewellery houses, Robert Goossens, the goldsmith and designer which the brand takes its name from, created big, semi-precious designs for Elsa Schiaparelli in the 1940s, Chanel in the late 1950s, then Yves Saint Laurent, Thierry Mugler and Karl Lagerfeld in the decades beyond. Goossens, which is also famed for its studio-made interiors designs, is still family-run but has been owned by Chanel since 2005. Regardless of the era, its designs are always spot on and seriously well priced. The house is currently gearing up for the arrival of Matthieu Blazy, who will make his debut as creative director in July.

Stella McCartney, of course, is already in tune with the costume-jewellery revival. Her Paris SS25 show, Save What You Love, featured a moulded, gold-plated bra and sizeable, sculptural necklaces. She devised the pieces in collaboration with 886 by The Royal Mint’s creative director Dominic Jones. Each jewel, which is available now across McCartney’s boutiques, was traditionally modelled in wax then cast in repurposed silver and plated in gold extracted from electronic waste.

These production details tell you much about the difference between costume and retail fashion jewellery – the design and techniques of the latter, though imagined by a designer, are generally mass-produced. Costume jewellery, meanwhile, is created in a traditional workshop setting using classic assemblage techniques. Its base elements, such as the gilt settings, chains and links that hold the jewellery together, are generally designed in-house and acquired from trusted casting houses. On the whole, though, the designs are brought to life at the jeweller’s bench, while the materials, which might include elements such as crystals, faux pearls and semi-precious stones, are carefully sourced and hand-worked.

Expert finishing, including layers of non-tarnish gilt plating and high-quality fastenings, is what really sets good costume jewellery apart. It’s worth noting, though, that neither fashion nor costume designs should be confused with the creation of demi-high or high jewellery, which, due to the extremely precious nature of the highest-quality gold, platinum and rare gemstones, can require a specialist, museum-detail approach. Jewels made in highly valuable metals and stones are serious commodities and still a form of personal banking for some – a way to carry wealth on the move. The non-precious nature of costume jewellery, however, not only makes it highly affordable but seriously collectable, too.

Shaun Leane, who’s best known for his groundbreaking 17-year collaboration with Alexander McQueen, is a classically trained jeweller. He neatly summed up the differences between jewellery types during a conversation I had with him a couple of years ago. He recalled how, when they were young, Lee would come to meet him at work in London’s Hatton Garden before they went out. The fashion designer was always keen to get there early so he could watch Leane at work, intricately repairing vintage Cartier pieces at the bench.

So fascinated was McQueen by Leane’s traditional goldsmithing techniques, in fact, that he asked him to collaborate on jewellery pieces in line with his collection designs. Leane recalled how, at the time, he wasn’t interested. He was reluctant to create what he considered “fashion jewellery”. And when he realised that McQueen envisaged him working, as usual, in precious materials, Leane was shocked. “I said to Lee, ‘Look, I work in gold, diamonds, emeralds. How can I do this? How big would they have to be? They’d be too heavy. Where will we get the money? It’s impossible!’” Though gold and gemstones were out of the question (gold is a weighty metal, apart from anything else), Leane found himself drawn to the scale of McQueen’s ideas and started to experiment with different metal types to achieve what he had envisaged. Together, they took catwalk jewellery to new creative heights.

Having worked across all levels of jewellery design, from fashion to catwalk, fine and high, Clare Corrigan, a creative consultant and former design director at Marc Jacobs, is well versed in their differences. “When you look at original fashion costume jewellery, it is the exquisite rendering, the materiality, the proportions, the way that a closure has been incorporated, that really draws you to it,” she says. “Whether it’s a metal-based chain or a costume pearl, if the materials – semi-precious onyx, rock crystal or resin, say – are approached as you would precious elements, the result is very beautiful, luxurious jewellery.”

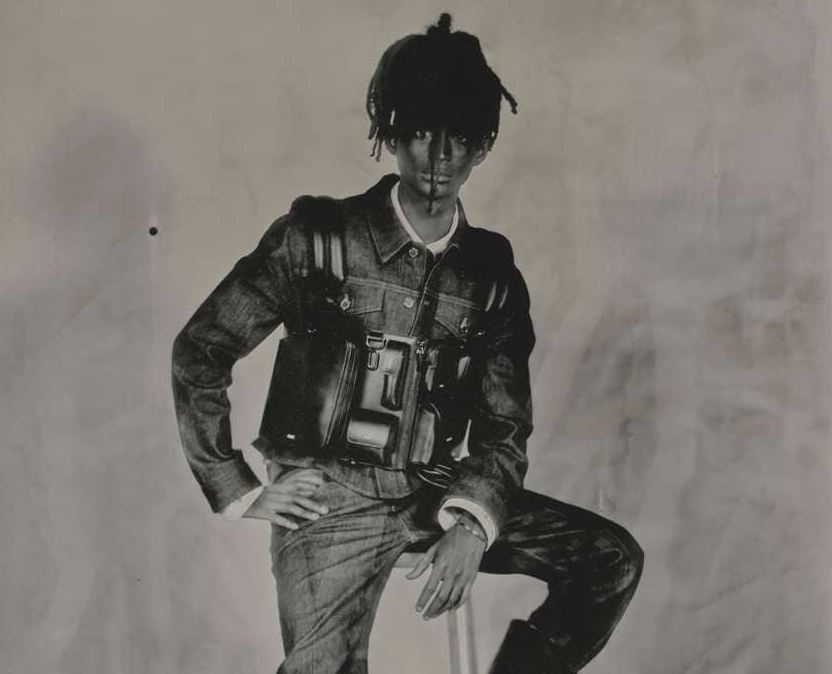

Having spent nearly a decade as a jewellery director with Jacobs in the 2000s and a lengthy stint as a senior ready-to-wear designer in the late 1990s with Karl Lagerfeld (for whom she would collect flea-market jewels), Corrigan’s recent design credits include last year’s jewellery collections with Louise Trotter at Carven (though she’s now at Bottega Veneta) and Grace Wales Bonner at her eponymous label. For the latter’s SS23 show, the pair, “hunter-gatherers both”, looked at Corrigan’s collection of original bauhaus jewellery. “One of the jewels I designed for that collection – a little purse necklace in bone sequins, inlaid with a pearl – drew on the rhythm of an Anni Albers embroidery design,” says Corrigan. “And as Grace had just come back from Ghana, we were looking at the amazing glass beads she had found, which were created using a pâte de verre [glass paste] style that the other great Parisian costume jeweller, Gripoix, was known for.”

Beads, rather than rhinestones (which demand a whole essay of their own), are arguably the diamonds of costume jewellery. Erickson Beamon, noted for its starry collaborations with fashion directors and costume designers since the early 1980s, made its name with opulently beaded costume styles. Co-founder Vicki Sarge left the business in 2013 to work in her eponymous Belgravia boutique for a while. Her brand returned to life with the opening, last summer, of a new boutique in Kensington Church Street, where Vogue’s Hamish Bowles was on hand to cut the ribbon. It was also a celebration to announce that Sarge has passed the beaded baton to its two new, young owners, 26-year-old Louis Circé Mehra and his husband and business partner Rahul, with Sarge staying on as special consultant.

Circé Mehra, a former burlesque performer and jewellery devotee, was mentored by Sarge, who took him on as showroom manager. Though not a jeweller, he is a graduate of the GIA (Gemological Institute of America). “When Vicki announced her retirement, we didn’t want to see her legacy wasted,” he tells me, as we look at the new collection in the brand’s home. Starry Night, inspired by the van Gogh painting, is a magnetic array of classical-tinged designs rendered in gold-plated silver and black and white crystals, with prices starting at a somewhat undervalued £150 for the bracelet.

This year will mark four decades of Sarge’s career. “We have almost 40 years of sketches, memos, notes, everything relating not only to VickiSarge collections but to the house’s work with Givenchy, Galliano, Dior, Chanel and all the others,” Circé Mehra says. “It will be a privilege to revisit some of these creations.” And, as is the way of traditional costume-jewellery makers, the boutique has a workshop installed in the basement, where students trained at Central Saint Martins and other schools are employed at the start of their own jewellery-design journeys.

The London-based artist Leix Wu is one of them. Her “monster” jewellery is a response to her view of female complexity. But in practical terms, it is viscerally, intricately compelling. The polished silver pieces are joyfully magnetic and have a molten, creeping quality that is designed to create, bit by gleaming bit, a carapace for one’s finger or wrist. Another designer, Aeolus Studio, creates collections in sterling silver with a sparkling creativity and quiet humour that carries over to lifestyle objects, too. These include an analogue-camera lens cover, a cigar stand and a drum key in the shape of a torso.

Costume-jewellery design often comes to life with a slinky humour attached, as the humble, lightweight materials allow for unbridled expression. As Corrigan points out, “During the stock market crash in the 1930s and the world wars, people were experimenting and making jewels with what was to hand. Cork, newspaper and surrealist interventions, such as cellophane, which reflects light and so creates its own feeling of opulence, are just some of the materials that people found a new creative purpose for.”

In that spirit, Elsa Triolet, the Russian writer, activist and modernist, designed witty costume jewels for Schiaparelli, including the Aspirin necklace, a string of simple, porcelain beads in which she saw a resemblance to the pills and, no doubt, a soothing message. “There needs to be an element of fun in what I make,” says the East London-based jeweller Toby Mclellan, who is self-taught and trained in Hatton Garden. His Instagram bio says it all: “Can make anything, within reason.”

“A lot of what I create is different from mass-produced factory pieces,” he says. “It’s all crafted in traditional ways, by hand, from wax modelling to polishing and engraving.” Though many of Mclellan’s jewels are precious-based, he does create costume and non-precious designs, too. “I enjoy making bold, playful, symbolic pieces, so working with base metals, such as brass, means I can design [works] for events and music videos.” A recent client request was a case in point. “A female singer asked me to create a silver and gold microphone cover for a karaoke party.” It was a commission perfectly in sync with Mclellan’s preference for making “bold, playful, symbolic” work. And, as he says, “Pieces like these are a fraction of the cost of using precious metals. Don’t get me wrong – I do appreciate subtle pieces, but for me, jewellery is about making an impact. I like to wear jewellery, and I like to look at it, too.” Bold as brass.

Taken from 10 Magazine UK Issue 74 – MUSIC, TALENT, CREATIVE – on newsstands now.