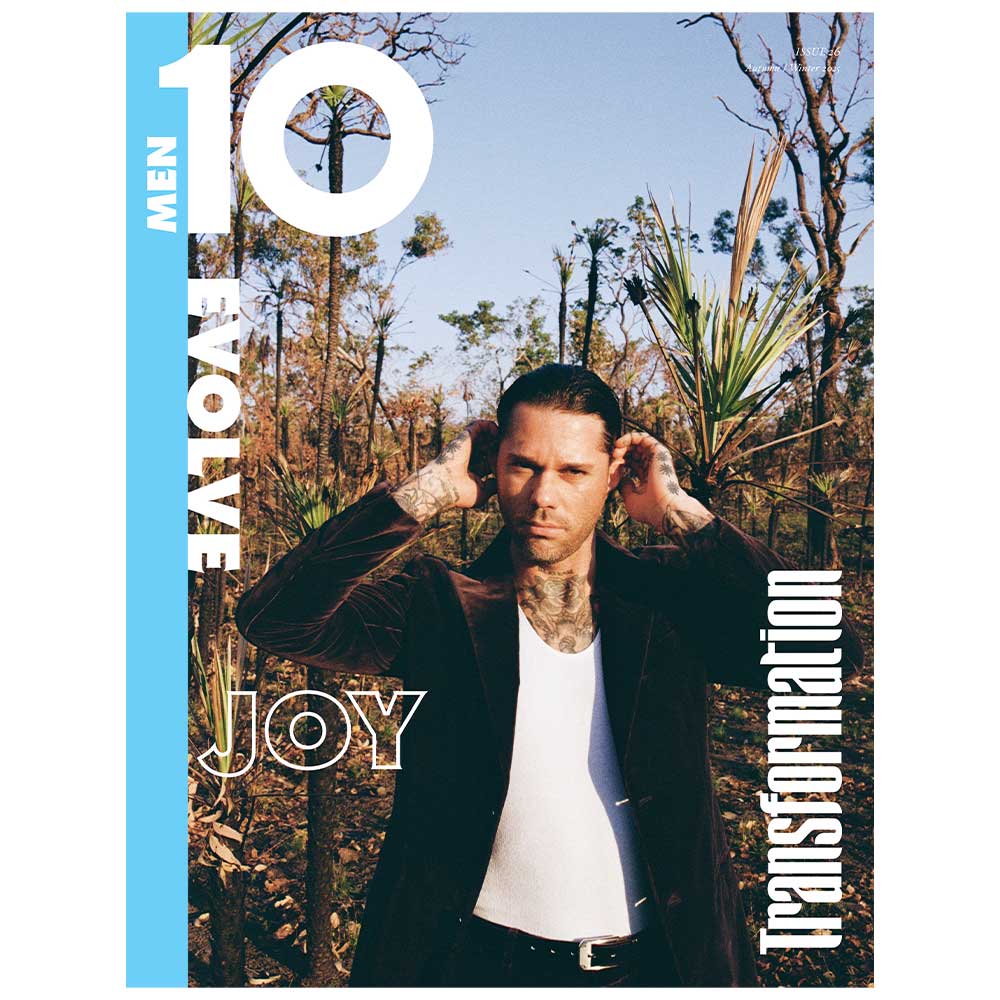

FROM THE ISSUE: BEFORE SUNSET

Written by Ariela Bard and taken from Issue 26 of 10 Men Australia - TRANSFORMATION, EVOLVE, JOY - on newsstands today.

When I meet the artist Shaun Daniel Allen, better known as Shal, on a midweek morning at the Surry Hills gallery China Heights, Sydney is primed for an extreme weather event known as a bomb cyclone. But there is no rain in sight and the bright winter sun is streaming through the trees, which are still clutching onto a few of their autumn leaves, and into the studio, where Shal is unravelling a length of rust-coloured fabric from a suitcase.

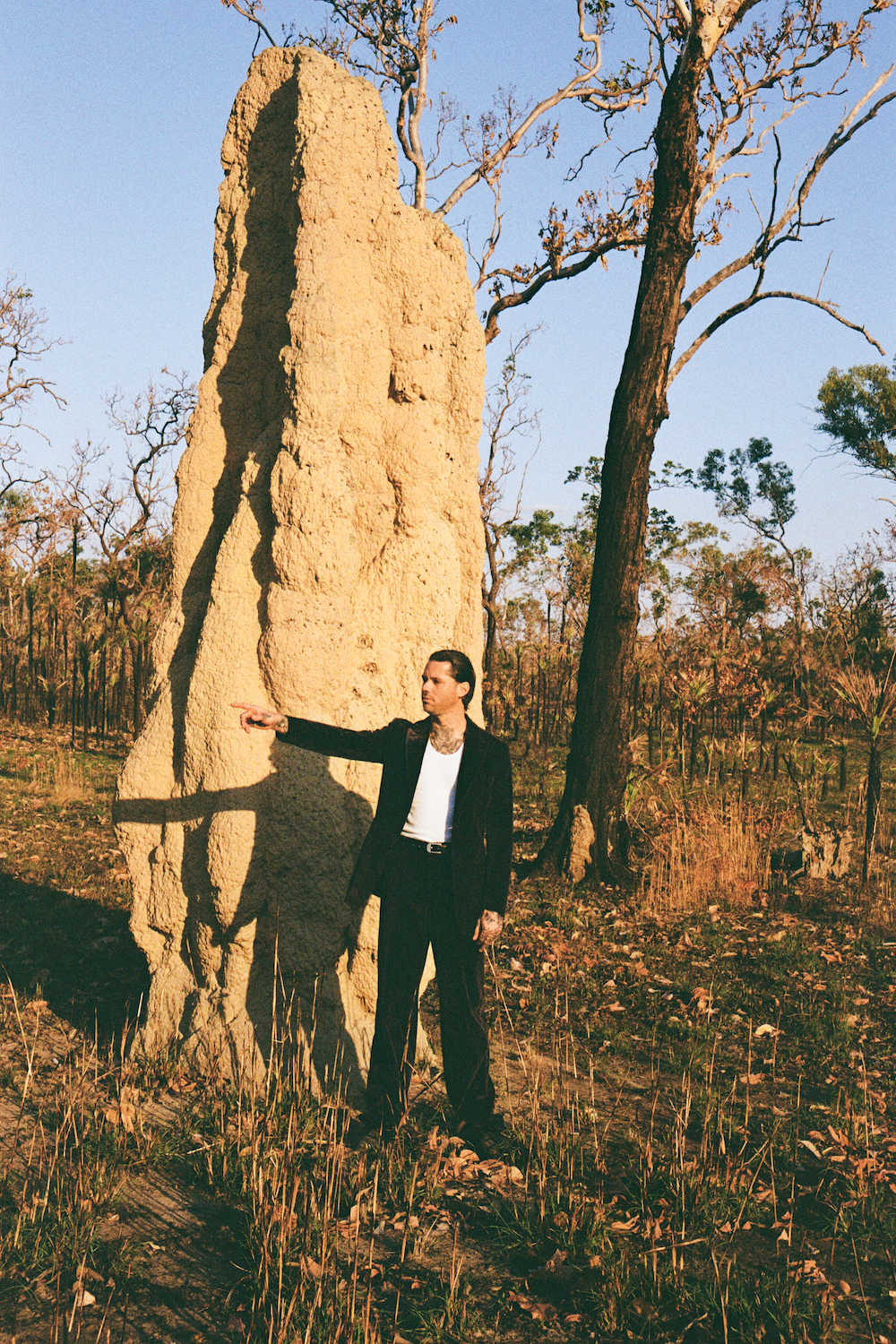

He has just returned from Darwin, where he spent time sourcing tree roots to create dye from scratch, and as he unfurls the fabric he finds small pieces of sediment that he rolls tenderly between his tattooed fingers. Shal, a 39-year-old Bundjalung man living on Gadigal land, has been exhibiting with the Surry Hills gallery since his sold-out debut solo show in 2021. The owners, Edward Woodley and Nina Treffkorn, have a diverting collection of art books, over which Shal and I linger before taking advantage of the break in the weather to walk through the backstreets of Darlinghurst to his studio in Taylor Square. Shal tells me that he loves books, zines and catalogues. Anything a friend has made and put into the world he has kept. But he’s also getting into Audible and listened to a slew of audiobooks while he dyed the textiles for his next series, a collaboration with the luxury brand Hermès.

“I loved Dolly Alderton’s book Everything I Know About Love,” he says. “Then I listened to all her stuff.” I can already see that Shal has a soft and gentle manner – he’s earnest and sincere, and speaks thoughtfully and quietly. But I can’t say that I’m not a little surprised that the former tattooist and frontman of two hardcore punk bands has just made his way through the oeuvre of the British podcaster and rom-com writer. He laughs when I tell him it wasn’t the answer I was expecting. He knows it’s incongruous and it’s immediately clear to me that he’s impossible to pigeonhole.

“As a teenager, I got deep into listening to both Bob Dylan and [the death metal band] Cannibal Corpse in the same week. My mum was like, ‘What is going on!?’” In his studio, which is beautifully organised with tubs of pigments and dyes, dried leaves, mortars and pestles (where he grinds ochre), and an array of impressively clean brushes, I cast my eyes over the ephemera he has pinned to the wall. His painting influences range from Monet’s Water Lilies through to Kaylene Whiskey and Albert Namatjira. He tells me that he makes playlists for each body of work that he creates and that his friends are often mystified by his eclectic tastes. I ask him to send me some, which he does, and I listen to them while I write this piece. I love the way he veers from The Cure to Brisbane’s Strange Motel and then back around to The Cure (we both really like them).

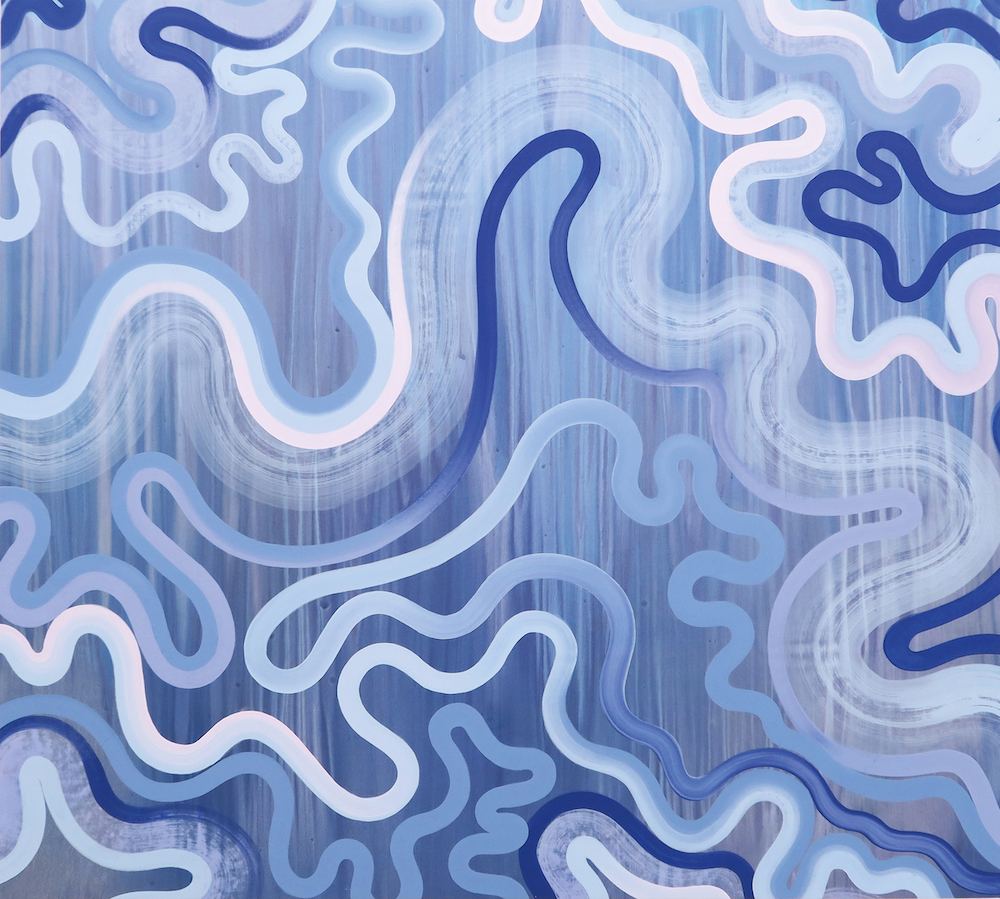

“Music has always been a big part of my life. It’s something I’ve never stopped doing,” he tells me. Growing up on the Gold Coast, Shal spent his early teen years surfing before discovering the local punk scene and falling in and out of local bands. He got jobs working in tattoo stores, which he did for 10 years, before learning the art himself. “It was either that or lose my job,” he says. “My boss said I should learn to tattoo or get out! And I really needed that 220 bucks a week.” The precision required for a tattoo artist strikes me as a far cry from the fluid, evocative gestures that are characteristic of his paintings, which call to mind sun-kissed rivers and craggy, ancient rockscapes. Shal credits his move from tattooing to painting to his friend Josh Roelink, a fellow artist and tattooist. “He told me about meditative painting. That you can put brush to paper with no plan, just to make marks. At the time I was still trying to paint something that was more tattoo-related. And when I’d get to the end I’d feel like, ‘It’s not perfect so I don’t like it…’ When I started making paintings that had no ending and no purpose, it slowly started to change. And in a way I’m still in the midst of that evolution. I never really set out with a finished idea in mind. I just see what happens.”

“Every now and then someone comes along and you just know they’re the real deal,” Woodley says. “When I first saw Shal’s work I was struck by the raw emotion expressed in such a constrained fashion. It’s almost like he’s a vehicle for something else. Those lines didn’t necessarily appear to have been made by a person, more a force.”

Shal cites the painter Daniel Boyd as key to his evolution as an artist too. Shal’s mother lives near HOTA (Home of the Arts) on the Gold Coast and he says he started going to the gallery every day to stand in front of Boyd’s work. He says he couldn’t quite believe his eyes as he tried to make sense of it. “I started bothering him on Instagram, tagging him in pictures, saying, ‘What the hell… how do you do this?!’” He laughs at his own chutzpah. After moving to Sydney he wrangled an introduction to Boyd and has since spent time working as his assistant. “He’s an unbelievable man, so kind. Everything he says just holds so much weight. He’s helped me in a million different ways.”

While Shal no longer tattoos, the music he’s always played is still very much a part of his life (he plays in two punk bands, Nerve Damage and Primitive Blast). “It feels like a real contrast to the painting. People come to my shows and say, ‘The work is so calm… But then the music is chaos, energy, noise.’ And I think that’s the point. We all have different sides. It’s just rare to have the outlets to express them all. I feel really lucky to have both. I tend to hyper-focus. When I’m in a band, I give it everything. Then I swing back to painting and give that everything. It’s a cycle and they feed into each other.”

At the moment, Shal’s hyperfocus is on the fabrics that will end up in the windows of the Hermès store in Sydney and on his show at China Heights in November. He has taken a characteristically sincere and earnest approach to the Hermès collaboration, travelling to Darwin to work alongside Aunties Nunuk and Regina Wilson from the Durrmu Arts centre in Peppimenarti, 186 miles southwest of the Northern Territory’s capital city. “The aunties showed me how to collect roots from a few different trees – you only take enough so that you don’t kill the tree. You wash it down, scrape it, break off all the flesh and then boil it down in large pots to extract the colour. Then you put the fabric in.” He let the fabrics dry out under the harsh Territory sun and will soon set about painting them on the studio floor at China Heights. “All this could have been achieved with dye from a bottle,” he tells me. But his raw and tactile approach was received well by the fashion house, which understood and supported his vision.

It’s not the first time Shal has collaborated with a global luxury brand. In 2023, Louis Vuitton dedicated a floor of its multi-level Brisbane boutique to an exhibition of his paintings. Soon after, the Swiss watch and jewellery maison Chopard came knocking and he designed a limited edition of the brand’s Alpine Eagle watch. Earlier this year, he created a large-scale immersive experience for Nike’s annual Air Max Day. I wonder what it is about his work that is so appealing to luxury brands.

“Shal’s work is unique in the sense that you can dissect it and work out how it’s created,” Woodley says. “It’s so sincere, passionate and immediate. What that means is that a lot of people can connect with it, yet it still has a unique voice.”

For his collaboration with Hermès he will be transforming the store into a landscape inspired by the rocks from Sydney’s coastal bays. “Everything that would have been there before the city was built,” he says. But it’s also clear that this new work is imbued with the landscape of the Northern Territory, where bright, hopeful bursts of purple lotuses appear among the otherworldly orange hues of the ancient earth under a vast and unrelenting blue sky. Shal maintains that he can find country wherever he is. “I homed in on a lot of the colours I was seeing throughout the trip. But every landscape I walk across inspires and directs my work in certain ways. Country is still there, in between buildings, in the trees and flowers trying to push through the concrete. In the escarpments and the rocks…”

He likes to swim at Sydney’s MacKenzies Beach and there is something fitting about that – the ephemerality of the diminutive stretch of sand that disappears every few years and continues to mystify experts.

“I have always been drawn to the water,” he tells me. “Sometimes when I’m floating I’m the only person there.” I’m about to ask him if he’s literally the only person in the water, or if it just feels that way. But then he says, “The calm and peace I find in the ocean is the same calm and peace I find through painting.” And we leave it there.

Photographers RYAN DER and NINA FITZGERALD

Stylist SHAL

Text ARIELA BARD

Clothing throughout by HERMES